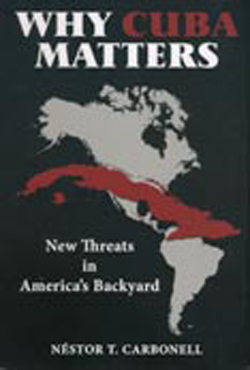

Join the author, Néstor T. Carbonell, as he shares a critical analysis of the Castro-Communist regime

and explores the challenges and opportunities that will likely arise when freedom finally dawns in Cuba.

CHAPTER 4: In the Eye of the Storm: Denouncing the Takeover (1959-Mid-1960)

Willauer was deeply worried about the progressive Castro-Communi control of Cuba. He viewed it as a clear and present danger.

On January 26, 1959, he had shared his concern with his friend Jose Figueres Ferrer, the short but gutsy former president of Costa Rica who had supported the Castro insurgency with arms and ammunitions, and urged him to weigh in, along with other leaders of the «Democratic Left» who also had helped to put Fidel in power. Willauer was referring to the newly elected president of Venezuela, Romulo Betancourt, and the governor of Puerto Rico at that time, Luis Munoz Marin.

After consulting with his Latin American confreres, Figueres agreed to approach Castro at the earliest opportunity. Invited by Fidel to attend a major labor rally in late March, Figueres flew to Havana and tried to meet with him beforehand, but the Maximum Leader had no time for him. Figueres did not take that as a snub. In the spirit of camaraderie, he arrived at the rally clad in his revolutionary attire—the overseas cap, khaki shirt, and trousers he had worn to fight the forces of tyranny in his country—and was greeted by the crowd with an ovation.

The climate changed dramatically, however, when in the course of his laudatory speech Figueres broached a delicate but, in his mind, defining issue. He essentially framed it this way: «Whatever you may feel about liberalism or communism, there is a Cold War going on, and Latin America must be on the side of the US and against Russia in a showdown between those two sides.»

Pandemonium broke out when he uttered those words. I watched the televised rally in astonishment as the Cuban labor chief, David Salvador, grabbed the microphone away from Figueres and blasted him. Then Fidel took over and humiliated the former Costa Rican president, accusing him of being a reactionary and a false friend with intolerable imperialist tendencies. Relentless in gushing vitriol, he then thrashed US corporations, which in their greed, he claimed, had killed more Cubans than had Batista.5

Upon his return to San Jose, Figueres commented to Willauer: «We have no doubt that this matter [the Castro revolution] is a Communistmatter …; if it is not already, it is about to be.» Ambassador Bonsai did not see it that way. He attributed the serious incident not to ideology or allegiance but simply to Fidel’s «extreme sensitivity to advice even from a friendly source.»6

CASTRO’S TRIP TO THE UNITED STATES (APRIL 1959)

Nothing that Castro did or said during the first four months of his sweeping revolution seemed to have marred his visit to the United States, which he adroitly turned into a charm offensive. Invited by the American Society of Newspaper Editors to deliver a keynote address, he arrived in Washington donning his signature olive-green fatigues and high black boots, and was besieged by photographers and reporters and hailed by his ecstatic admirers.

He told the Society of Newspaper Editors and other audiences in Washington and New York basically what they wanted to hear: that he was not a Communist; that his revolution was «humanistic»; that he welcomed foreign investments and would not confiscate American properties; and that he would respect the freedom of the press—»the first enemy of dictatorships,» he proclaimed—and hold open elections.

Even though Castro arrived with his entire economic team, he left with empty pockets. Had the US government turned its back on him, offering no financial assistance to the revolution? And was this seeming rebuff, as many «blame America» observers alleged, one of the main reasons why Castro turned to the Soviets for support? Rufo Lopez-Fresquet, Cuba’s minister of finance who accompanied Fidel during the trip, put this myth to rest when he defected two years later.

Lopez-Fresquet disclosed what actually happened: «[Fidel] warned me as we left Havana not to take up Cuban economic matters with the [US] authorities. … At various times during the trip, he repeated the warning. That is why, when I visited the then secretary of the Treasury, Robert B. Anderson, I did not respond to the American official’s indications that the United States was favorably disposed ward aiding our country.

«Also, for this reason,» continued Lopez-Fresquet, «when I changed views with Assistant Secretary of State for Latin Americ Affairs Roy Rubottom, I feigned polite aloofness to his concrete stat ment that the US Government wished to know how and in what fo it could cooperate with the Cuban Government in the solution of the most pressing economic needs.»7

Lopez-Fresquet explained why Castro did not seek, or accept, US aid. «If the US had helped Cuba, he could never have presented the Americans as enemies of the revolution.» Felipe Pazos, president of the National Bank of Cuba, who also accompanied Fidel and was barred by him from pursuing the International Monetary Fund’s overtures, concurred with Lopez-Fresquet’s views.

During the trip, not everyone was totally convinced that Castro and his revolution was not Communist. One of those who harbored some doubts was Vice President Richard Nixon, who privately met with Fidel in Washington for more than two hours. According to a summary of the conversation filed by the State Department (April 1959), Nixon noted that «Castro was either incredibly naive about communism or under Communist discipline.» His guess, however, was the former. In any case, he concluded, «We have no choice but at least to try to orient him in the right direction.»

A high-level CIA official who secretly met with Fidel in New York did not share Nixon’s ambivalence. The official was the German-born CIA veteran Gerry Droller (alias Frank Bender), who later formed part of the task force that spearheaded the Bay of Pigs operation. After Droller’s three-hour meeting with Castro, arranged by Rufo Lopez-Fresquet, Droller went to Rufo’s hotel suite «in a state of euphoria. He asked for a drink, and with great relief exclaimed: ‘Castro is not only not a Communist, but he is a strong anti-Communist fighter.'»8

It seems that Droller bought Fidel’s spiel (the same that had bewitched Rufo): «I am letting the Communists stick their head out so I know who they are. And when 1 know them all, I’ll do away with them, with one sweep of my hat.»

CASTRO’S SHADOW GOVERNMENT

The contention that Castro did not have a Communist game plan when he visited the United States, which most historians still hold, is contradicted by reliable testimonies. Juan Vives (a nom de guerre), a well-informed Castro secret service defector now residing in France, wrote: «On March 3, 1959, at the offices Che Guevara had at La Cabana [fortress], Fidel Castro held a private meeting with Fabio Grobart, the Comintern’s secret envoy to Cuba since 1927. … This truly secret conference went on from 2:45 to 5:30 in the morning. I recall the date and time because that day I was on duty and I recorded all those details on the registry. The next morning, Che tore the page with the annotations and told me not to make any comments.»9 Vives further disclosed that following this meeting, five Cuban Communist leaders left for the Soviet Union and Red China on a secret government mission.

The most startling revelation, however, was that, unbeknownst even to his own Council of Ministers, Castro had operated a shadow or parallel government with the Communists from the time he took power—an undercover scheme akin to his ideology and duplicitous personality. As confirmed by Fidel’s biographer Tad Szulc, based on extensive interviews in Cuba, this secret network functioned on two levels simultaneously.

On one level were the old Communist hierarchs (including the wily Fabio Grobart) who dealt primarily with the phased and bumpy integration of Castro’s 26th of July Movement and the Socialist Popular (Communist) Party. The process, which gave rise to purges, clashes, and defections along the way, reached its first official milesttmCin 1961 with the formation of the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations.

Blas Roca, the historic leader of the Socialist Popular (Communist) Party, commented to Szulc that when they secretly met with Castro to design the strategy in early 1959, Fidel laughingly exclaimed as he took a puff on his cigar, «Shit, now we are the government and still we have to go on meeting illegally.»10

On the other level was a separate task force, carrying as a cover the innocuous name of the Office of Revolutionary Plans and Coordination, which was composed of young Marxist leaders of the 26th of July Movement (including Raul Castro and Che Guevara). They met at Che’s beach resort in Tarara, some ten miles east of Havana, and later at Fidel’s nearby villa in Cojimar—both spacious properties confiscated by the «austere» regime.

Among the foreign Communists who joined the Tarara group was Angel Ciutah, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War who was close to Ramon Mercader, the Catalan who murdered Leon Trotsky in Mexico. The Kremlin reportedly sent Ciutah to Havana, along with Luis Alberto Lavandeira, to help the Castro regime set up a police state backed by a G2 repressive body modeled on the Cheka, the Soviet organization charged with rooting out counterrevolutionary activities.»

Che Guevara took charge of G6, the agency that oversaw the Communist indoctrination of the officers of the rebel army, which Raul Castro had started during the insurgence in Sierra Cristal.12

Among the other Leninist initiatives pursued by the Tarara group, the most salient ones were the Agrarian Reform Law and the revolutionary militias charged at the outset with the enforcement of that law. Their main task was to «intervene» (euphemism for seize) the private farms that were to be converted into state cooperatives a la Chinese communes.

CASTRO’S FAILED INTERNATIONAL FORAYS I (APRIL-AUGUST 1959)

As Castro rolled out his broad-scale domestic agenda, he did not forgo his far-reaching international goals. Since he took power, he was determined to export his revolution or, as he later put it, turn the Andes into the Sierra Maestra of Latin America. To do that, he needed more arms, so the first thing he asked his newly appointed minister of finance, Rufo Lopez-Fresquet, in January 1959, was to use the $5.3 million left by the Batista regime in European banks to purchase automatic FAL rifles, ammunitions, and grenades from Belgium.13 This, less than two weeks after Fidel had delivered his «Arms for What?» inaugural speech at Camp Columbia, chastising the members of the Revolutionary Student Directorate for not disarming.

A little later, the Castro regime provided refuge and military training to young leftist rebels from several Latin American countries. Some of them secretly trained in the hacienda of my grandfather Cortina in the far-western province of Pinar del Rio, without his knowledge.14 Between April and August 1959, four small armed expeditions were launched from Cuba to overthrow or destabilize the governments of Panama, Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

The US ambassador did not attach much importance to these flagrant acts of intervention, confirmed by an OAS investigative committee. He apparently did not realize that these amateurish and failed attempts to export the Cuban Revolution were but a prelude to the major Castro-led subversive campaign that would rock the continent for more than three decades.

THE FIRST MAJOR CONSPIRACY AGAINST THE CASTRO REGIME (AUGUST 1959)

Anti-Castro Cubans who maintained close relations with US Embassy staffers were generally aware that Ambassador Bonsai—a keen practitioner of constructive engagement—opposed taking a firrrr’stand against the Castro regime, but they never imagined that he would be a whistle-blower. Declassified State Department documents suggest that the ambassador conveyed to Cuban authorities confidential information on the first major conspiracy against the Castro regime, which was foiled in early August 1959.

Led on the civilian side by a former labor minister, Arturo Hernandez Tellaeche, and by the president of the National Cattle Ranchers Association, Armando Cainas-Milanes, the planned uprising was backed by several former officers of Cuba’s standing army (pre-Castro), as well as by two chiefs of the rebel army, Eloy Gutierrez Menoyo and an American adventurer with a shady background, William Morgan. The «Americano,» as Morgan was called, fought against the Batista forces in the Second Front of the Escambray Mountains and rose to the highest rank of comandante.

Key units of the aviation and tank divisions were reportedly involved in the plot, which received military aid from Trujillo, the Dominican ruler. This was his way of reciprocating Castro’s sponsorship of the recent foray on Santo Domingo.

According to declassified State Department documents, Ambassador Bonsai informed Washington on August 3 that he had advised Castro’s foreign minister, Raul Roa, of the planned uprising and of Morgan’s involvement, based on an FBI report. Bonsai further stated that «on August 4, [he] called on Roa at the latter’s request. Roa said that he had conveyed the information on Morgan to President Dorticos, who was ‘highly alarmed.’ Apparently, Castro has not yet been given the information, according to Roa.»15

In his memoir, Bonsai explains that his tip-off was prompted by his «worries … for the safety of resident Americans because of the possible impact of the Castro tirades about the evil intentions of the United States.»16 He also wrote that an attempt was made to induce a young embassy official to meet with some of the conspirators before they were caught, but no such meeting took place. This assertion is flatly contradicted not only by several cattle ranchers who reportedly shared information on the plot with embassy officers, but also by Paul Bethel, the ambassador’s own press attache.

As related in his book The Losers,17 Bethel received in late June a mysterious call from Morgan, who whispered on the phone, «Come to my house early tomorrow morning.» Bethel had met Morgan and Menoyo

when they both visited the embassy a few months earlier and provided details on the progressive Communist takeover of the Castro regime.

Given the urgency of the message, Bethel went to see Morgan at the mansion given to him by the revolutionary government in the swank residential section of Miramar. Dressed in his rebel army uniform, bearing the one-star rank of comandante, the tough, squat, blue-eyed «Americano» greeted Bethel like a «long-lost brother.»

As they walked in the garden, Morgan suddenly turned to Bethel and said: «I have five thousand men, willing and able to fight against communism … Castro is a Communist, see, and we don’t like Communists. I told you about this before. Well, we’ve been working to get our people into strategic spots.» He then ticked off several «coman-dantes» and captains who «are with us.»

After answering a few probing questions posed by Bethel, Morgan became a little nervous, wondering whether he had been wise to divulge «all this information» to him. Bethel assured him, as he swiftly left the house through the garden, that «embassy officers had no obligation to become a source of intelligence for the Cuban government.» It didn’t cross Bethel’s mind that the gist of the long memorandum of the conversation that he wrote and gave to the deputy chief of the CIA in Havana would later be leaked by the ambassador to the Castro regime.

It is still an open question whether Morgan acted as a double agent throughout the process or only when Castro confronted him with general foreknowledge of the conspiracy. On the basis of all the evidence gathered by the embassy, Bethel wrote, Morgan was indeed plotting against Castro. But when Morgan learned that certain of his conspiratorial activities had been brought to the attention of the Maximum Leader, he spilled the beans to save his skin and told Fidel that he had been acting as a double agent to gather as much information as hcfould on the plotters. As a result of these developments, the planned uprising was quashed. More than one thousand conspirators were rounded up and imprisoned.

Morgan and Menoyo (who also flipped over) were declared heroes

0 comentarios