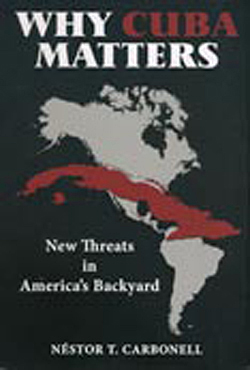

Join the author, Néstor T. Carbonell, as he shares a critical analysis of the Castro-Communist regime

and explores the challenges and opportunities that will likely arise when freedom finally dawns in Cuba.

CHAPTER 7: The Battle of the OAS and the Mongoose Plots (Mid-1961- Early 1962)

The Bay of Pigs Fallout (April-May 1961)

On April 21, 1961, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara met with the Joint Chiefs of Staff to assess the impact of the Bay of Pigs failure. He urged them to accept appropriate responsibility and avoid backbiting. He also disclosed that the president was going to establish a high-level committee to reexamine the entire operation and make recommendations.1 This committee, known as the Cuba Study Group, was chaired by General Maxwell D. Taylor.

Attorney General Robert Kennedy didn’t wait for the formation of Maxwell Taylor’s committee, which he joined, to express his strong views on the ill-fated invasion and its fallout. Not having been directly involved in the Bay of Pigs operation, he did not want to remain on the sidelines on matters pertaining to Cuba and national security.

On April 19, the same day the Bay of Pigs brigade, encircled by Castro’s tanks and abandoned by the United States, fired its last shots, the attorney general wrote a memorandum to the president calling for a new muscular policy toward Communist Cuba. He stressed that «the immediate failure of the rebels’ activities in Cuba does not permit us… to return to the status quo with our policy toward Cuba being one of waiting and hoping for good luck.»

In light of the failed invasion, Robert Kennedy argued that «Castro will be even more bombastic, will be more and more closely tied to communism, will be better armed, and will be operating an even more tightly held state than if these events had not transpired.» To address the looming danger, the attorney general mentioned possible actions, from a US armed intervention in Cuba (which had been ruled out) to a military blockade of the island, preferably in concert with other members of the OAS.

The memorandum ended with this prescient warning: «The time has come for a showdown, for in a year or two years the situation will be vastly worse. If we don’t want Russia to set up missile bases in Cuba, we had better decide now what we are willing to do to stop it.»

Robert Kennedy’s assessment of the Castro-Communist imbroglio (after the United States had missed a great opportunity to end it) was prompted by genuine concern. But it also reflected anger over the humiliation the Bay of Pigs disaster had brought to his brother. He described it in his memorandum as an affront to the nation: «the US having been beaten off with her tail between her legs.»

The following day (April 20), the cabinet meeting convened by the visibly shattered president turned out to be a painful and rather chaotic postmortem of the Bay of Pigs—everyone jumping on everyone else. The attorney general was the toughest in his comments, mostly directed at the State Department. When Undersecretary of State Chester Bowles, sitting in for Secretary Dean Rusk, took exception to Robert Kennedy’s stinging reproach, the attorney general turned «savagely» on him.

The liberal undersecretary, a Yale graduate who had made a fortune in advertising and later served as governor of Connecticut, congressman, and ambassador to India, did not take Robert Kennedy’s zinger lightly. With a condescending tone, he characterized the attorney general and Vice President Lyndon Johnson in his notes on the cabinet meeting as newcomers «with no experience in foreign affairs,… involving complex politics, economics, and social questions that require both understanding of history and various cultures.» And yet, according to Bowles, both were «determined to be experts at it.”

The undersecretary of state would soon be eased out of his job, whereas Robert Kennedy became his brother’s closest confidant, adviser, and partner, wielding considerable clout in foreign affairs, particularly on Cuba. He is believed to have been one of the instigators of the president’s directive to the Defense Department «to develop a plan for the overthrow of the Castro regime by the application of US military force.»

The plan, as summarized in Secretary McNamara’s April 20 memorandum, was to include, among other things, an appraisal of the Cuban military forces; an analysis of alternative programs for accomplishing the objective, for example, a complete naval and air blockade versus an armed invasion; and a detailed statement of the US forces required. As a safeguard, the memorandum pointed out that «the request for this study should not be interpreted as an indication that US military action against Cuba is probable.»

The president seemed interested in pursuing this matter, and on April 29 he met with Admiral Arleigh Burke and Secretary of Defense McNamara to review Contingency Plan I for the Invasion of Cuba by US troops. The plan envisioned a first wave of approximately sixty thousand troops, excluding naval and air units, and required twenty-five days of preparation from date of decision to D-Day. Complete control of the island would take about eight days, save for some anticipated guerrilla resistance in the mountains. The president concurred in the general outline and asked to prepare the detailed instructions necessary to implement the plan.

Then, in less than a week, the president shifted gears. At the meeting of the National Security Council held on May 5, he put on hold all the military plans against the Castro regime and decided to pursue a nonconfrontational policy recommended by the State Department. The new Cuba policy called for intelligence gathering, propaganda (but no electronic warfare), censure and isolation of the Castro regime by the OAS, and economic aid to Latin America through the Alliance for Progress to contain the spread of Castro communism.

To placate the Cuban exiles, who blamed Washington for the Bay of Pigs disaster, it was agreed that US relations with the Cuban Revolutionary Council—the leading anti-Castro organization headed by José Miró-Cardona—should be improved and made more open but without recognizing the Council as a government-in-exile. It was also agreed that Cuban Americans should be encouraged to enlist in the US Army, but a separate Cuban military force was ruled out

The declassified State Department documents make no reference to two meetings with exile leaders that likely accounted for the inclusion of the Council-related items in the new Cuba policy. Thanks to the notes taken by Ernesto «Bebo» Aragon, Miró-Cardona’s executive assistant and interpreter who attended both meetings, we learned what happened.

According to Aragon’s records, handed to me prior to his passing, after Miró-Cardona and other Council leaders had rounded up the Bay of Pigs survivors in Central America and the island of Vieques, they were summoned to Washington for a high-level parley with US government officials. The meeting was held on May 2 in a private conference room at the Park Sheraton Hotel. Representing President Kennedy were Paul Nitze, then assistant secretary of defense, and Richard Goodwin, a thirty-year-old Harvard Law School graduate who had started with Kennedy as a speechwriter and soon became a special presidential assistant in charge of the task force on Cuba. (His purview was later expanded to cover Latin America.)

The exile leaders thought that the main purpose of the May 2 meeting was to discuss new plans for the liberation of Cuba. The president’s emissaries, however, had a different agenda. Goodwin stated that he and Nitze were there at Kennedy’s request to discuss the fate of the brigade prisoners and survivors, and the assistance to the families of the deceased. That was well received. But when Goodwin indicated that the agenda also included the relocation of Cuban refugees based in Miami—a sensitive issue perceived as a deliberate attempt to disperse and weaken the exile community—the Cuban leaders exploded in anger.

Before the interpreter could translate, the Council representatives fired a string of rebukes in Spanish at their befuddled interlocutors: «We didn’t come here for this. We’ve been duped again. … It’s another betrayal. … We want military support, not relocation!»

Miró-Cardona managed to restore order and asked Goodwin to convey to the president that the Cuban Revolutionary Council was prepared to discuss the items on his agenda, but only after the liberation plans had been mapped out. Thereupon, he tersely ended the discussion and told the president’s envoys that he and his colleagues would return to Miami the following day.

Kennedy feared that the rift would flare up in public if not promptly and diplomatically defused. Two hours after the rowdy meeting had concluded, Goodwin called to inform Miró-Cardona that the president wanted to see him alone, but that Miró could bring his own interpreter if he wished.

The confidential meeting took place at the Oval Office on May 4. Accompanying Miró-Cardona was Aragon, who acted as interpreter for both his boss and Kennedy. According to Aragon’s notes shared with me, the president, all by himself at the Oval Office, greeted the exile leader warmly and sat in the rocking chair he used to ease his back problem, flanked by two small sofas occupied by his guests. He calmly lit a Havana cigar and commented that he was running out of them. Without missing a beat, Aragon said: «Mr. President, with all due respect, I hope you will exhaust your supply of Cuban cigars soon so that we can help you get some more.» Kennedy laughed heartily.

At the president’s request, Miró-Cardona ticked off the salient points covered in a memorandum in Spanish he handed to Kennedy: recognition of the Council as a Cuban government-in-exile; economic, technical, and military support to continue the struggle; reinvigoration of the underground movement; and recruitment and training of Cuban military units to serve as the vanguard of a future liberation force.

The president listened carefully and promised to review Miró-Cardona’s aide-memoire. He did advance, however, some pertinent observations. Kennedy explained why the United States could not recognize a government-in-exile, which, lacking territory and coercive power, could not exercise authority or command respect. He promised instead to back the Cuban Revolutionary Council and raise its profile in Washington.

To ensure good communications, the president told Miró-Cardona, «You and I should each designate a representative to discuss specific issues, forge consensus, and implement decisions. If our delegates fail to reach an accord, we should meet again.» The president designated Richard Goodwin as his representative.

Kennedy agreed to proceed with the recruitment and training of Cuban military units but within the Armed Forces of the United States. He also favored revitalizing the Cuban underground and suggested that the details of the program and of the financial and technical assistance to the Council be discussed by their respective representatives.

The president ended the fifty-minute discussion by reiterating his full support for the Council. He expressed the hope that the new entente would further the cause of a free Cuba. Miró-Cardona thanked the president and, escorted by Goodwin, left the White House with a much-needed boost to face the disgruntled exile community, which had not yet recovered from the Bay of Pigs shock. Although he left the Oval Office with only vague promises, Miro-Cardona felt he had developed a good rapport with the president and could reach out to him if things didn’t work out as planned.

The Thrashing of JFK in Vienna (June 1961)

JFK hoped that the specter of the Bay of Pigs would not haut him at the June 3-5, 1961, summit meeting in Vienna with Nikita Khrushchev or prevent a relaxation of tensions over Berlin. But that was not to be.

Cuba became a central issue, and the Soviet prime minister used it to lecture and hector the president and place him on the defensive.

Khrushchev derided Kennedy for attempting to halt the «unstoppable» spread of communism and for fearing Fidel Castro. «Can six million people really be a threat to the mighty US?» Kennedy, who meekly conceded that he had made a mistake with the Bay of Pigs, told aides at the end of the first day of the summit, «He [Khrushchev] treated me like a little boy.»

Having vowed to render the Castro regime all necessary help to repel any armed attack on Cuba, Khrushchev told Kennedy that he was planning to sign a treaty with East Germany that could effectively block access by the West to Berlin. To play up his threat, he cockily remarked, «If the US wants to start a war over Berlin, let it be so.»

Kennedy was taken aback by Khrushchev’s hostile rhetoric. Instead of warning the Soviet premier that the United States had the power (indeed the nuclear superiority) and the unflinching resolve to counter any threat to its security and international alliances, he nervously sought to avoid a confrontation. This hesitancy to take a stand, perceived as weakness, emboldened the Soviet ruler not only to clobber the president in Vienna but also to confront him later with a wall in Berlin and offensive missiles in Cuba.

When New York Times writer James Reston asked Kennedy in Vienna how it had gone with the Soviet premier, the president candidly replied: «Worst thing in my life. … He savaged me.» Then he added: «Because of the Bay of Pigs, Khrushchev thought that anyone who was so young and inexperienced as to get into that mess could be taken. And anyone who got into it and didn’t see it through had no guts. So he just beat the hell out of me. … I’ve got a terrible problem.»

What accounted for Kennedy’s pitiful performance in Vienna? As Frederick Kempe explains in his book Berlin 1961, the president ignored the advice of foreign policy experts and fell for the ploy of a Soviet spy, Georgi Bolshakov, who had «sold» to Bobby Kennedy his closeness to Khrushchev and lied about Moscow’s intent and game plan.

Bolshakov, a congenial bon vivant with a trace of black hair, piercing blue eyes, and strong Russian accent, had penetrated Washington’s social circles and gained the confidence of the attorney general prior to the Vienna meeting. Relying on Georgi’s good faith and trying to avoid misunderstandings during the summit, Bobby candidly relayed to the spy what the president wanted to avoid, namely, being viewed as spineless after the Bay of Pigs and being drawn into a heated discussion of Berlin’s status and what he desired to achieve—a nuclear test ban deal. With this valuable information, the Soviet leader was well prepared to pound the president where he was most vulnerable.

Kennedy’s stress, and its likely impact on emotion and judgment, was heightened by his severe back pain and battery of medications to alleviate it. The pain, intensified by an injury suffered during a tree-planting ceremony in Canada, forced him to use crutches, wear a back brace, and bring along to Europe not only his personal physician but also an unconventional medic, known as «Dr. Feelgood,» who lost his medical license years later. These two men administered to the president anesthetic procaine for his back, cortisone for his Addison’s disease, and a cocktail of vitamins, enzymes, hormones, and amphetamines. Between doses, Kennedy’s mood and demeanor swung from a high of overconfidence to a low of depression.

Bouts of despondency hit Kennedy hard in Vienna. When his secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, was filing the classified documents of the summit, she found a slip of paper on which the president had written these two lines: «I know there is a God—and I see a storm coming. If He has a place for me, I believe I am ready.»

I

The Alliance for Progress and Che Guevara’s Gambit (July-August 1961)

After his return from Vienna, Kennedy tried to turn the Bay of Pigs page and deemphasize the Cuban situation. After all, the island was not the center of the universe, and the president had other, more important

and more pressing issues to address. Yet the Castro regime remained a festering problem, and Moscow’s increasing involvement in Cuba was a cause for concern.

On July 11, an ad hoc committee of the United States Intelligence Board issued a detailed report on the arms buildup in Cuba, flagging that «the Soviet bloc continues to extend considerable military assistance to Cuba in the form of military equipment, training, and technicians and advisers.» The equipment included MiG aircraft and heavy tanks, and there were indications that the Castro regime would also receive Soviet jet bombers.

According to the intelligence report, the major Soviet military buildup in Cuba was designed to hasten the consolidation of the Communist regime «through the regimentation of the Cuban people under a police state» and to establish «a secure base of operations for furthering their aims throughout Latin America.»13

This report troubled the president and prompted him to pose pertinent questions to someone he respected for his straightforwardness and clear-eyed assessment of the Cuba situation: Admiral Arleigh Burke. Kennedy invited Burke to the White House on July 26, just before the admiral’s retirement, and they talked about Cuba. This is how Burke summarized the conversation in a memorandum for the record: «He [the president] asked me if I thought we would have to go into Cuba. I said yes. He asked would Castro get stronger. I said yes. Castro would increase his power over his people. He asked whether we could take Cuba easily. I said yes, but it was getting more and more difficult. He asked what did I think would happen if we attacked. I said all hell would break loose, but that someday we would have to do it.»14

Despite Burke’s advice, the president ruled out drastic action in Cuba and attempted to isolate the Castro regime and neutralize its destabilizing activities by promoting economic development and social reforms elsewhere in the hemisphere. The vehicle used was the Alliance for Progress, and the strategy pursued was to «avoid other

Cubas by attacking the root causes of communism: poverty, hunger, and social injustices.»

Although these were not the main causes that had catapulted Castro into power, few would quarrel with the lofty goals of the Alliance for Progress, which was to be fueled by $20 billion in US foreign aid over ten years. There was a problem, however, with this long-term development program that required business confidence and political stability to stimulate investments. The hitch was that if the Castro-Communist regime—promoter of subversion throughout the continent with Soviet backing—was not first eliminated, the alliance would degenerate into a futile race to see whether dollars poured in by the United States could outpace dollars taken out by frightened Latin Americans.

As a representative of the Cuban Revolutionary Council, I stressed to several US senators and congressmen the need to link the Alliance for Progress to an Alliance for Freedom. For if economic aid was not tied to a collective commitment to excise the Castro-Communist cancer, the leftist governments and demagogues in Latin America would most likely «court the radicals, take the dollars, and thank Fidel.»15

Still, the Kennedy administration went ahead with the formal launch of the Alliance for Progress at an inter-American conference held in Punta del Este, Uruguay, in August 1961. Cuba was represented by none other than Ernesto «Che» Guevara, who seemed to have undergone an ideological metamorphosis. Instead of spewing radical epithets, he sedated the conclave with the soothing bromide of peaceful coexistence.

Had the Marxist firebrand really changed, or was this a show, orchestrated by Castro, to dupe their enemies, lower their guard, and buy some time? Guevara’s record speaks for itself. During the insurgency against the Batista dictatorship, Guevara wrote to a Cuban underground chief, «I belong, because of my ideological background^jcv that group which believes that the solution of the world’s problem lies behind the Iron Curtain.»16

During the first five months of the Castro regime, while Guevara

0 comentarios